Written by my husband, Steve:

I had the honor and thrill of being the first Manager of Brimstone Hill Fortress National Park. It was a long journey to get to that place. From the abandonment of the fortress in 1854, to the formation of the Brimstone Hill Society in 1965, to national legislation formally designating the National Park in 1987.

By 1854, it became obvious to the British military authorities on St Kitts (and London) that the continued occupation and maintenance of Brimstone Hill was both unnecessary and infeasible. The decision was therefore made to abandon it. Easily transportable and usable items were removed as part of the abandonment, but the big guns and all the buildings/structures were left behind. However, just in case some old rival or new adversary might get any ideas, before departure, all the guns were spiked (actual spikes driven into the touch hole-where the fuse was lit) to delay or prevent future use, and then cast from the battlements down the slopes of the hill.

By 1854, it became obvious to the British military authorities on St Kitts (and London) that the continued occupation and maintenance of Brimstone Hill was both unnecessary and infeasible. The decision was therefore made to abandon it. Easily transportable and usable items were removed as part of the abandonment, but the big guns and all the buildings/structures were left behind. However, just in case some old rival or new adversary might get any ideas, before departure, all the guns were spiked (actual spikes driven into the touch hole-where the fuse was lit) to delay or prevent future use, and then cast from the battlements down the slopes of the hill.

The building materials were quickly claimed by the inhabitants and used for their own building projects. Aside from the vast array of fortifications spread over the hill, the fortress was also the designated sanctuary to where leading citizens were to flee if the island was again invaded. There were numerous “private” residences within the walls of the fortress reserved for particular families. As can be imagined, the removal of those structures in combination with the now uncontrolled encroachment of tropical vegetation, quickly reduced the fortress to ruins.

The building materials were quickly claimed by the inhabitants and used for their own building projects. Aside from the vast array of fortifications spread over the hill, the fortress was also the designated sanctuary to where leading citizens were to flee if the island was again invaded. There were numerous “private” residences within the walls of the fortress reserved for particular families. As can be imagined, the removal of those structures in combination with the now uncontrolled encroachment of tropical vegetation, quickly reduced the fortress to ruins.

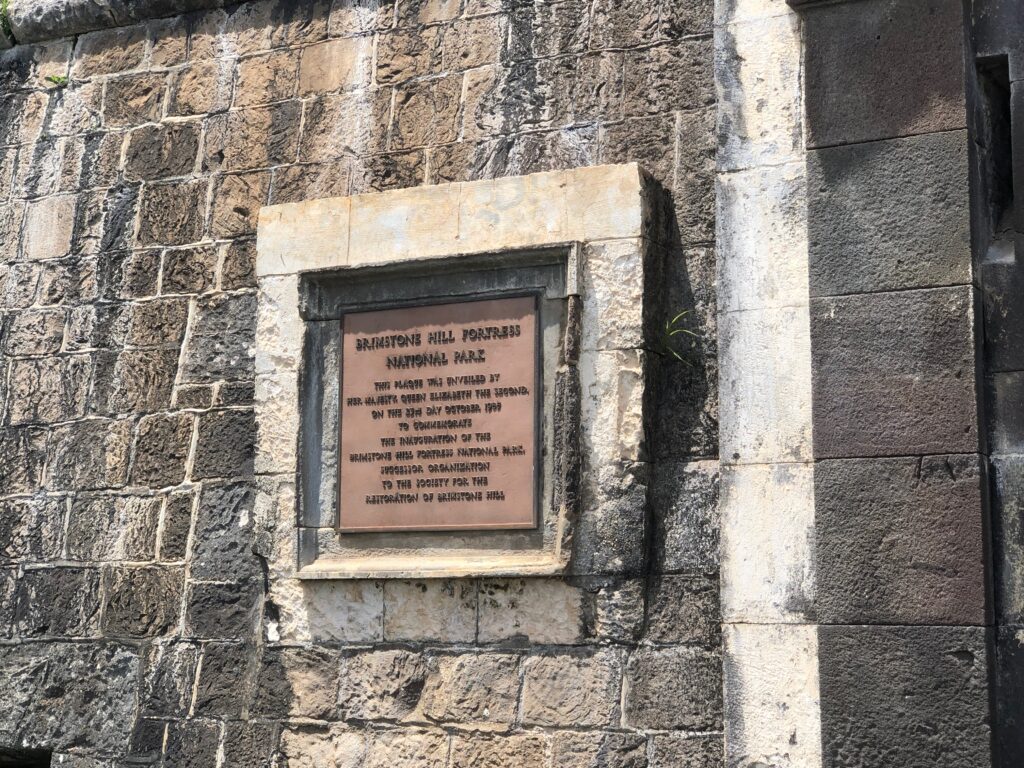

The fortress sat derelict until 1965 when the Brimstone Hill Fortress Society was formed. It was a non-profit organization dedicated to the restoration of the fortress. The first portion of the fortress to be restored was the Prince of Wales Bastion – dedicated in 1973 by Prince Charles, the Prince of Wales. In 1985, Queen Elizabeth unveiled a plaque declaring Brimstone Hill a National Park, and in 1987, national legislation was signed which officially designated Brimstone Hill a National Park.

There were two very significant aspects to that legislation. The first was that all monies collected from visitors to the park would remain with the park, the government would have no hand in setting a budget. The second was that it codified the role of a park manager.

There were two very significant aspects to that legislation. The first was that all monies collected from visitors to the park would remain with the park, the government would have no hand in setting a budget. The second was that it codified the role of a park manager.

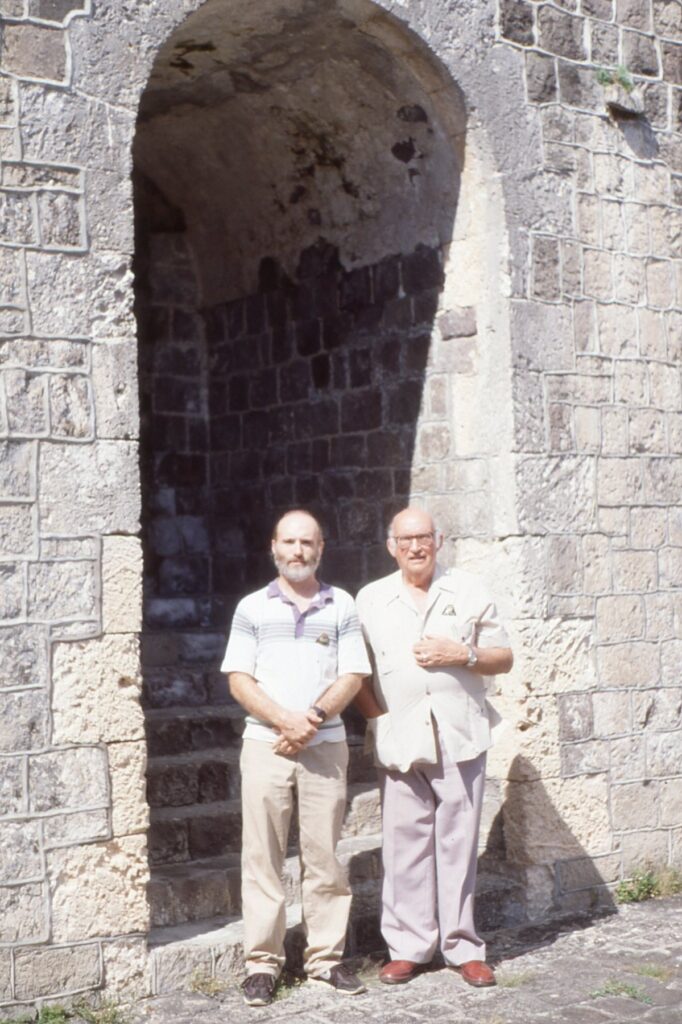

The head of the Brimstone Hill Society, Mr. D. Lloyd Matheson, knew that St. Kitts did not yet have anyone with the desired training and experience to be that manager, so he expanded his search beyond the island. That search resulted in an agreement with the U.S. Peace Corps, which was already present on St. Kitts and Nevis, to request a park manager be included in the next group of Volunteers. As a result of that request, I arrived in November of 1987 for my two-year stint on St. Kitts.

The great thing about being the first manager of a new national park is that I was able to identify needs and develop plans to address them. Until my arrival, and that of a fellow Peace Corps Volunteer who worked as the Park’s Museum Curator, visitors were essentially self-directed. Or, maybe the taxi drivers who brought the tourists would act as informal guides. One of the first things my colleague and I did was to formalize the visitor experience; that is, we were there to tell the story of Brimstone Hill. Mr. Matheson spent every Wednesday with us, but the rest of the week I was the sole park interpreter. It was quite the time on days when several hundred cruise ship passengers all descended on the park at once.

The great thing about being the first manager of a new national park is that I was able to identify needs and develop plans to address them. Until my arrival, and that of a fellow Peace Corps Volunteer who worked as the Park’s Museum Curator, visitors were essentially self-directed. Or, maybe the taxi drivers who brought the tourists would act as informal guides. One of the first things my colleague and I did was to formalize the visitor experience; that is, we were there to tell the story of Brimstone Hill. Mr. Matheson spent every Wednesday with us, but the rest of the week I was the sole park interpreter. It was quite the time on days when several hundred cruise ship passengers all descended on the park at once.

Because the fortress was located on top of an 800-foot-tall hill at the end of a 2-mile road, the Park Society purchased a little Suzuki van for my use. They were so generous in their desire to help, that I was allowed to use it 24/7 my entire two years there. I was the only Volunteer on the island allowed to drive, so in my off hours I also became the de facto Peace Corps taxi driver!

One requirement associated with the use of the van was that I was expected to be the first person on the Hill every day to make sure the road was passable. The road had been constructed in a zigzag pattern as it slowly snaked its way up to the Parade Ground. The road was narrow and the hillside steep. Many a morning, especially after a rain the previous evening, I would find the occasional cannonball, the shattered remains of a howitzer shell (both from the siege of 1782), broken clay pipes, dishware, or glassware washed onto the road from above. (I soon learned that refuse was thought of 200-years ago as it was today, if you threw it over the edge to where you could no longer see it, it was no longer a problem! I was finding 18th century garbage!). Fallen rocks were also a constant find in the road. One memorably painful morning, the ring finger on my left hand disturbed a non-too happy scorpion or centipede under the rock I was attempting to remove. I spent that morning in the Sandy Point hospital with a throbbing finger and numb arm, lips, and tongue! Fortunately, an antihistamine injection resolved the problem.

One requirement associated with the use of the van was that I was expected to be the first person on the Hill every day to make sure the road was passable. The road had been constructed in a zigzag pattern as it slowly snaked its way up to the Parade Ground. The road was narrow and the hillside steep. Many a morning, especially after a rain the previous evening, I would find the occasional cannonball, the shattered remains of a howitzer shell (both from the siege of 1782), broken clay pipes, dishware, or glassware washed onto the road from above. (I soon learned that refuse was thought of 200-years ago as it was today, if you threw it over the edge to where you could no longer see it, it was no longer a problem! I was finding 18th century garbage!). Fallen rocks were also a constant find in the road. One memorably painful morning, the ring finger on my left hand disturbed a non-too happy scorpion or centipede under the rock I was attempting to remove. I spent that morning in the Sandy Point hospital with a throbbing finger and numb arm, lips, and tongue! Fortunately, an antihistamine injection resolved the problem.

During my time there, we were able to reconstruct three structures based on the original plans (and built with original materials collected from strewn remains), and expose the ruins of many more. I was able to arrange for some informal archaeology before the buildings were rebuilt, and I led/directed the removal of extensive vegetation from areas that had not been free of trees for over 130 years. A visit by Hurricane Hugo in September of 1989 resulted in the inadvertent exposure of many previously obscured ruins (at the price of a blown over structure or two).

We opened a gift shop while I was there and I was responsible for closing it out each night and for managing the inventory. I encountered and tried to deal with the illegal removal of plants (aloe for traditional medical use) and the trapping of the resident green vervet monkeys (escaped from their origin as pets of the French during one of the British-French conflicts) and now numbering in the thousands throughout the island. I did a survey of historical graffiti found throughout the fortress carved into the limestone and andesite by bored and long-suffering soldiers (eventually published as an appendix to an article on the architecture of the fortress). I even wrote a series of articles extolling the virtues of national parks for the two national newspapers.

We opened a gift shop while I was there and I was responsible for closing it out each night and for managing the inventory. I encountered and tried to deal with the illegal removal of plants (aloe for traditional medical use) and the trapping of the resident green vervet monkeys (escaped from their origin as pets of the French during one of the British-French conflicts) and now numbering in the thousands throughout the island. I did a survey of historical graffiti found throughout the fortress carved into the limestone and andesite by bored and long-suffering soldiers (eventually published as an appendix to an article on the architecture of the fortress). I even wrote a series of articles extolling the virtues of national parks for the two national newspapers.

The most noteworthy undertaking, and the one of which I am most proud, is writing the initial proposal for Brimstone Hill’s inscription onto UNESCO’s list of World Heritage Sites. Mr. Matheson and I began that process in 1989 and felt we had a very solid case for its inclusion. Unfortunately, our enthusiasm partly blinded us to the proper process, so we were understandably disappointed when our efforts were rejected. It turned out that the issue was that a nomination such as ours needed to be officially sponsored by the Government of St. Kitts and not by the entity seeking inscription itself. The good news is that Brimstone Hill Fortress was eventually inscribed in 1999. The sad news is that Mr. Matheson had passed away a couple of years previously and I had long since returned to the States. But it was based on our initial work and that is a source of great satisfaction.

The most noteworthy undertaking, and the one of which I am most proud, is writing the initial proposal for Brimstone Hill’s inscription onto UNESCO’s list of World Heritage Sites. Mr. Matheson and I began that process in 1989 and felt we had a very solid case for its inclusion. Unfortunately, our enthusiasm partly blinded us to the proper process, so we were understandably disappointed when our efforts were rejected. It turned out that the issue was that a nomination such as ours needed to be officially sponsored by the Government of St. Kitts and not by the entity seeking inscription itself. The good news is that Brimstone Hill Fortress was eventually inscribed in 1999. The sad news is that Mr. Matheson had passed away a couple of years previously and I had long since returned to the States. But it was based on our initial work and that is a source of great satisfaction.

There were many other things I worked on/developed while there, but suffice it to say that my two years on St. Kitts as Manager of Brimstone Hill Fortress National Park was a wonderful experience, a wonderful location, I made wonderful new friends, and now have a lifetime of wonderful memories.

There were many other things I worked on/developed while there, but suffice it to say that my two years on St. Kitts as Manager of Brimstone Hill Fortress National Park was a wonderful experience, a wonderful location, I made wonderful new friends, and now have a lifetime of wonderful memories.